From Excited Beginnings to Survival Mode: Our First Week as Spanish Colonists

"Mrs. Zema, are we going to die?"

This question came from Riley, our usually logical Military Committee member, as we wrapped up Day 5 of our Founding St. Augustine simulation. What started with excitement about "getting to be Spanish leaders" had transformed into genuine concern for their colony's survival.

After five days of navigating 16th-century crises, my twenty-two fourth graders had learned what every historical leader discovers: good intentions aren't enough when facing real-world challenges.

The Honeymoon Phase Ends Quickly

Days 2-3 felt like a successful adventure. Students were engaged, Pedro Menéndez's primary source letter fascinated them, and choosing their city location sparked passionate but manageable debates. Our morale tracker sat comfortably at 25 points—right in the middle, representing cautious optimism among the colonists.

The committees were finding their groove:

Military was focused and strategic

Town Planning asked thoughtful questions about infrastructure

Religious brought up concerns others missed about Native relationships

Everyone seemed confident they could handle whatever colonial life threw at them.

Then came Day 4.

When Reality Hits: The October 1565 Crisis

The El Explorador newspaper for October 1565 changed everything. Suddenly, my Spanish colonists weren't making one neat decision—they were juggling multiple urgent crises:

French troops preparing for attack at Fort Caroline

Food supplies running dangerously low due to storm damage

Housing shortages with families still living in tents

Growing tensions despite some Timucua agreeing to accept Spanish priests

Watching the committees grapple with this was fascinating. For the first time, they couldn't find an obvious "right answer."

Military Committee wanted to attack the French immediately: "Every day we wait, they get stronger!"

Town Planning was horrified: "But people are starving and living in tents! We can't start a war when we can barely take care of ourselves!"

Religious Committee worried about relationships: "What if the Timucua think we're too violent? They're helping us with food!"

The debate was intense. Emma and Alex from Military got genuinely frustrated when other students didn't see the French threat as the top priority. Sarah from Town Planning emerged as a strong advocate for "taking care of our people first." Sophia and the Religious Committee kept bringing the discussion back to long-term consequences.

After twenty minutes of heated discussion, they voted to stockpile food and build more housing—choosing immediate survival over military action.

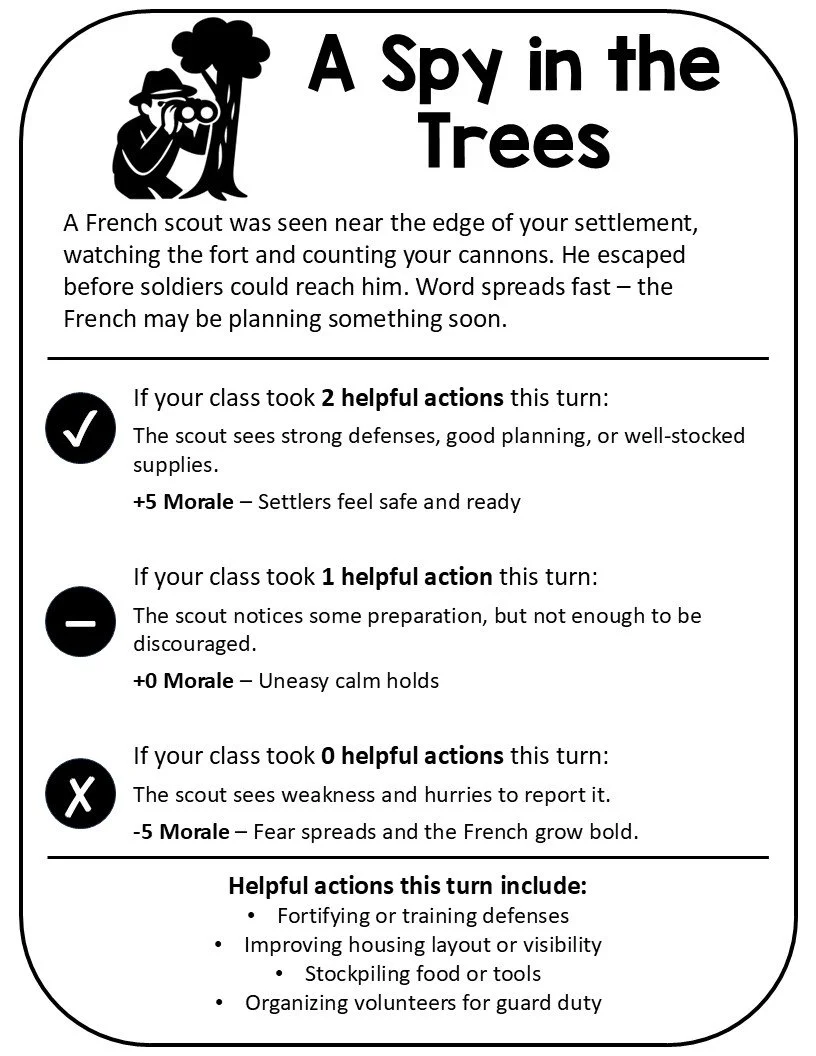

Then I revealed the day's event: "A Spy in the Trees."

"A French scout was seen near the edge of your settlement, watching the fort and counting your cannons. He escaped before soldiers could reach him. Word spreads fast—the French may be planning something soon."

The Military Committee exploded.

"SEE?!" Emma practically shouted. "We TOLD you we should have been training militia and building defenses! Now they know exactly how weak we are!"

Alex was shaking his head: "They counted our cannons! They know we're not ready!"

The rest of the class went silent. Their choice to focus on food and housing meant the French scout saw a colony that wasn't prepared for military action. Our morale stayed steady (they had taken some helpful actions), but barely.

The Morale Tracker Becomes Real

The "Spy in the Trees" event was a watershed moment. For the first time, students could see the immediate consequences of their strategic choices—and the Military Committee had proof they'd been right to worry.

But here's what made the discussion even richer: the other committees didn't just admit defeat.

"Wait," said Marcus from Town Planning, "but if we hadn't focused on food and housing, would our people have been too weak and sick to fight anyway?"

Sarah added: "And if the French had attacked and found us starving in tents, wouldn't that have been even worse?"

Sophia from Religious Committee brought up a point that surprised everyone: "Maybe the scout also saw that the Timucua were helping us with food. That might make the French think twice about attacking."

For the first time, students were seeing the historical reality that leaders face: there are no perfect choices, only trade-offs and consequences. The Military Committee had been "right" about the spy threat, but the other committees had been "right" about the survival issues too.

Day 5: When Everything Falls Apart

Just when they thought they had things figured out, the Late Fall 1565 newspaper arrived:

Housing shortages continued despite their efforts

Storm season extended with heavy rains and stronger winds

Food harvests remained small after storm damage

French reinforcements arrived, making the military threat even worse

Timucua provided emergency food aid but remained watchful

This time, the committees were less confident. You could see the weight of leadership settling on their nine-year-old shoulders.

Zoe, typically optimistic, looked worried: "It feels like everything we try to fix creates a new problem."

Jordan, usually quick with jokes, was serious: "This is really hard. I didn't think being a leader would be this stressful."

The Moment It Clicked

The breakthrough came when Miguel, who often struggles with traditional lessons, made a connection that stunned everyone:

"You know what? This is like when my family moved here from Puerto Rico. My parents had to make really hard choices about money and jobs and where to live, and sometimes there wasn't a good choice. They just had to pick the best one they could and hope it worked out."

The classroom went quiet. Other students started making similar connections:

Carlos: "My grandmother always talks about leaving Cuba and how scary it was not knowing if they made the right choice."

Sarah: "When my dad lost his job, my parents had to decide between moving closer to family or staying here. They weren't sure either choice was right."

Suddenly, Pedro Menéndez wasn't just a historical figure. He was someone facing the same kinds of difficult decisions their own families had navigated.

What I'm Learning as Their Teacher

Watching students engage with the simulation over five days has reinforced why I moved away from traditional social studies materials:

Textbook approach: Students learn that St. Augustine was founded in 1565, then move to the next topic.

Simulation approach: Students understand why it was challenging to found St. Augustine, how leaders made difficult decisions with limited information, and what the human cost of those decisions looked like.

The difference in engagement is remarkable. On Day 5, students were asking to take the El Explorador newspapers home to show their families. They wanted to discuss their committee strategies during lunch. They were invested in outcomes because they were making the decisions.

The Challenge That Surprised Me

The hardest part hasn't been managing the simulation mechanics or the content complexity. It's been helping students sit with uncertainty and ambiguity.

Nine-year-olds want clear answers: who are the good guys and bad guys, what's the right choice, how do we know if we're winning?

But historical leadership—like real leadership—rarely offers that clarity. The Spanish colonists weren't villains or heroes; they were people trying to survive in a difficult situation while balancing competing priorities and incomplete information.

Teaching students to think historically means teaching them to hold multiple perspectives simultaneously, to understand that different groups had legitimate but conflicting needs, and to see how individual decisions shaped larger historical patterns.

That's sophisticated thinking for fourth graders, but they're rising to the challenge.

Looking Ahead

As we head into week two of the simulation, our morale tracker shows a colony that's surviving but struggling. The students understand that they're not playing a game where smart choices lead to easy wins—they're experiencing the reality of how difficult it was to establish a permanent settlement in 16th-century Florida.

Next week, we'll jump ahead to 1573 and see how their colony has developed over time. Then we'll face the ultimate test in 1586 when Sir Francis Drake attacks St. Augustine with the full force of the English navy.

Will their early decisions about housing, food, and relationships help them survive? Will they have learned enough about leadership and compromise to handle the challenges ahead?

One thing I know for sure: they'll never forget that St. Augustine was founded in 1565, because they lived through the experience of founding it.

Ready to help your students experience the challenges of historical leadership? Discover the Founding St. Augustine simulation and see how primary sources and roleplay transform social studies from memorization to meaningful experience.